Suicide rates continue to increase above historical averages. Whatever we as mental health professionals are doing is not leading to winning the battle for better outcomes.

The reasons are several and complex. First, psychiatry’s ability to positively affect suicide rates is limited. For example, Luoma and colleagues reviewed 40 studies that reviewed patient contact with primary care and psychiatric providers within one month and one year before patients’ death by suicide.1 They found that within one year of death, 77% had had a visit with a primary care provider and 32% with a psychiatric one. And that within one month of death, 45% had had a visit with a primary care provider, and only 19% with a psychiatric one.

Thus, many persons who die by suicide never come to the attention of a psychiatric practitioner, or, of those who do, they do so months or years before their deaths. Clearly, to be able to make a large, meaningful positive impact on suicide rates, it must include mobilizing primary care providers and systems outside of health care, such as schools, the military, courts, social work, and other systems.

A second major hurdle to decreasing deaths by suicide is the current impossibility of predicting suicide. We know that the presence of a mental illness increases the risk of death by suicide up to 20 times, but, given the high rates and absolute numbers of people suffering from mental illness, this finding does not do enough to allow us, as a profession, to narrowly target the individuals to prevent their deaths.2

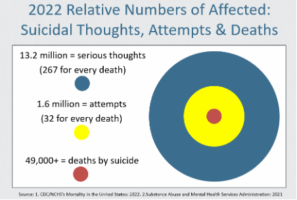

The graphic below illustrates the dilemma. Note that there were over 13 million individuals in the US (as estimated through epidemiological studies) who endorsed serious thoughts of suicide at any time in the year 2022, and about 1.6 million who made a suicide attempt that same year.

And, last, in that same year, the US saw over 49,000 deaths by suicide.3 Although this number of deaths is large, it is nevertheless still a very low percentage of the number of people at high risk of suicide, as evidenced by endorsing thoughts of suicide. In fact, for every person who died by suicide that year, there were about 267 people who endorsed serious thoughts of suicide. And, of course, there is no way of knowing whether that person who died by suicide would have been in the group of 13+ million who endorsed suicidal thoughts. Yes, some suicides are not preceded by thoughts of suicide. They are instead impulsive, ill-considered acts.

Now, if we only focus on the highest risk group – those who made a recent suicide attempt – we find that for every person who died by suicide, there were 32 people who attempted suicide. And, again, there is no way of knowing whether a person dying by suicide would have made a recent suicide attempt and been one of the 1.6 million. Most people dying by suicide have not made a previous attempt.

The operative statistical concept here is positive predictive value. In cases in which the outcome of concern is rare, as death by suicide is (49+ thousand a year in a population of about 330 million), any test or measure, even if highly sensitive and highly specific, will still identify only a small percentage of those who will go on to experience the adverse outcome (suicide in our case). Additionally, a majority of those testing positive on this predictive test or measure will be false positives, meaning they will not die by suicide. Given the rate of suicide in the US, even a test with 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity will still only identify about 20% of the people who will go on to die by suicide, and when they will do so.4

Given that currently we, as psychiatric professionals and as a society, cannot predict suicide, the question is how can we prevent it? Phrased differently: how can a professional, no matter how skilled and vigilant, prevent the unpredictable?

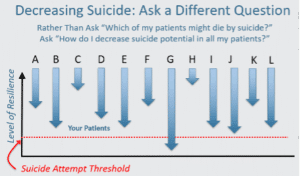

There is an answer to this dilemma, and I illustrate it in the two graphics below. The answer is to think of suicide prevention differently. We know that patients with psychiatric conditions are at increased risk of suicide, but we don’t know which ones or when they will do so. Even they themselves do not know. Many deaths by suicide are due to acute triggers on top of chronic risk factors, and acute triggers are not always predictable.

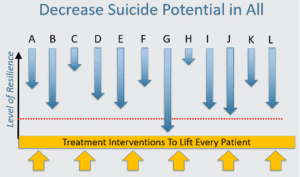

So, the way we deal with this difficulty is by decreasing the risk of poor outcomes, including suicide attempts and deaths by suicide, in each and every one of our patients.

How do we work with our patients to decrease their risk of suicide? The good news is that there are several approaches, including improving treatment adherence, therapeutic engagement, and deployment of the right medications, psychotherapies, and other forms of treatment with evidence of decreasing the suicide risk. Also, there are approaches to helping the person prepare for times of future increased risk and triggers. It’s a form of relapse prevention therapy.

The graphic below shows that if we have a group of patients, labeled A through L, perhaps one patient will make a suicide attempt. In the graphic, this patient is labeled ‘G’, but in real life, we don’t know who the patient who will act is. So we try to lift up all our patients, and we do so through optimizing their treatment.

If you’d like to learn more about suicide statistics, assessment, and management approaches, please avail yourself of my free Suicide Assessment and Management Course. Click here to learn more and sign up for it for FREE.

References

1. Luoma, Jason B., Catherine E. Martin, and Jane L. Pearson. “Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence.” American Journal of Psychiatry 159.6 (2002): 909-916.

2. Harris, E. Clare, and Brian Barraclough. “Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis.” British journal of psychiatry 170.3 (1997): 205-228.

3. Garnett, Matthew F., and Sally C. Curtin. “Suicide mortality in the United States, 2002–2022.” (2024).

4. Farberow, Norman L., and Douglas MacKinnon. “Prediction of suicide: A replication study.” Journal of personality assessment 39.5 (1975): 497-501.

Leave a Reply